Case of the Week #640

(1) Polish Mother's Research Institute, Department of Genetics; (2) Department of Obstetrics, Perinatology and Neonatology, Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education, Bielański Hospital, Warsaw, Poland; (3) Centro Médico Recoletas, Valladolid, Spain

A 33-year-old nullipara with non-contributory medical history presented at 20 weeks, 6 days based on an early scan. Ultrasound revealed the following findings. There were no other apparent abnormalities. What is the most probable diagnosis?

View the Answer Hide the Answer

Answer

We present a case of fetal hypothyroidism diagnosed at mid-trimester ultrasound.

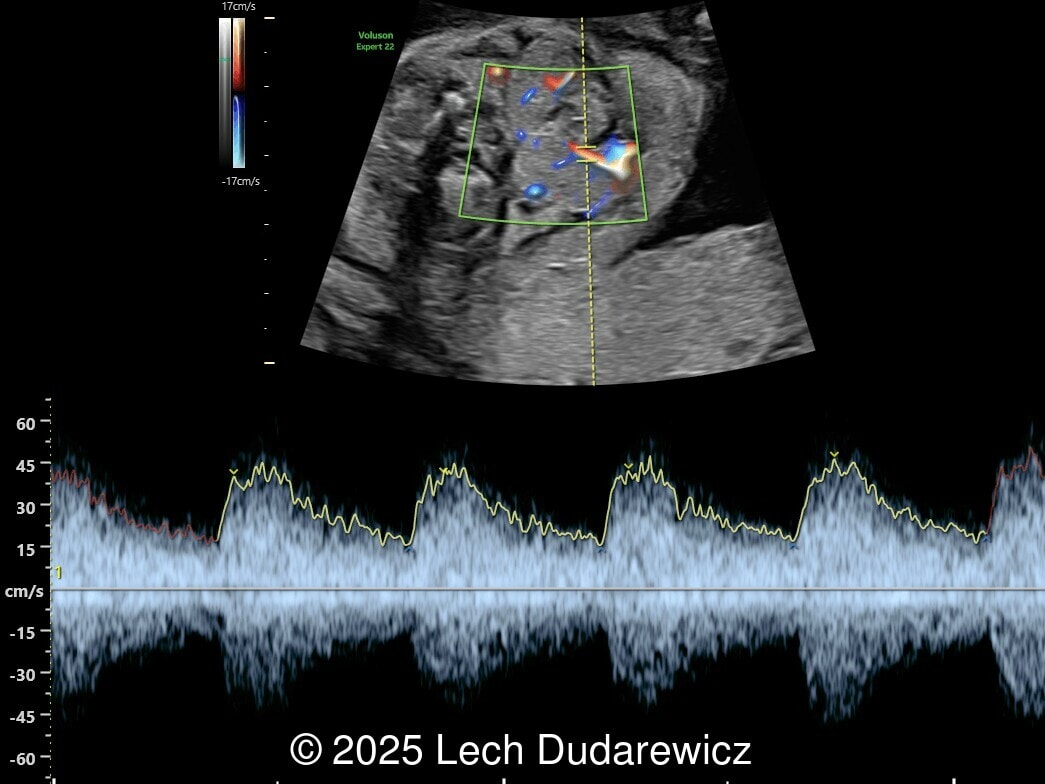

Ultrasound images demonstrated a symmetrically enlarged thyroid gland that was isoechoic to slightly hyperechoic relative to the surrounding tissues. Color Doppler revealed peripheral hypervascularization of the thyroid, known as the “peripheral vascular rim sign”. No internal parenchymal hyperperfusion was noted. Amniotic fluid volume was within normal limits and no structural anomalies were observed in the remainder of the scan.

The ultrasound findings were suggestive of severe congenital hypothyroidism. Additional prenatal workup was discussed with the family including maternal thyroid function testing, as well as fetal blood sampling (cordocentesis) to confirm fetal TSH and free T4 levels. If severe hypothyroidism was confirmed on cordocentesis, intra-amniotic levothyroxine therapy was proposed. The patient declined invasive prenatal testing and prenatal therapy.

The pregnancy progressed uneventfully. After birth, neonatal thyroid function tests confirmed congenital hypothyroidism. The newborn was started on oral levothyroxine therapy with good biochemical response.

Discussion

Fetal goiter is an enlargement of the thyroid gland, defined on ultrasound as a homogeneous, echogenic, symmetric mass in the anterior portion of the fetal neck [1]. It is the clinical manifestation of fetal thyroid gland dysfunction, which can be influenced by the maternal thyroid condition. Most cases are associated with maternal hyperthyroidism (Graves’ disease), but there are reports of fetal goiter in euthyroid mothers [2-4]. The effects of fetal thyroid goiter are both mechanical (mass effect) and biochemical [1, 5]. Due to the size and location of the mass, possible (though rare) complications include esophageal and tracheal compression, which can lead to polyhydramnios, dystocia during delivery, and neonatal respiratory compromise. The functional effects of thyroid goiter depend on its hormonal production. Most cases of hypothyroidism are asymptomatic until birth, presenting with impaired motor and intellectual development in later stages of life. In contrast, fetal hyperthyroidism presents with intrauterine growth restriction with accelerated bone maturation, tachycardia, and heart failure.

Although the global incidence of congenital hypothyroidism ranges from 1 in 2,000 to 1 in 4,000 newborns [6,7], the prevalence of hypothyroid goiter is much lower, only 1 in 35,000-40,000 newborns, with even fewer goiters associated with hyperthyroidism [1]. Congenital hypothyroidism is one of the most common preventable causes of intellectual disability worldwide [8]. In most cases, the disorder results from an abnormality in thyroid gland development (dysgenesis, 85% of cases) or an inborn error of thyroid hormone biosynthesis (dyshormonogenesis, 10-15% of cases). Secondary or central congenital hypothyroidism may occur with isolated thyroid stimulating hormone deficiency, but more commonly is associated with congenital hypopituitarism. Less commonly, the altered neonatal thyroid function is transient, attributable to the transplacental passage of maternal medication, maternal blocking antibodies, or iodine deficiency or excess [9,10].

Prenatal ultrasound is the preferred method of screening for head and neck masses. The first ultrasound diagnosis of a fetal goiter was made by Weiner et al. in 1980 [11], and since then several cases have been published, mostly isolated or small series [12,13]. Ultrasound can accurately assess the size, location, internal blood supply, and growth of the fetal goiter, as well as evaluating its effects on neighboring structures and amniotic fluid volume. Key sonographic findings include a homogeneous, echogenic, symmetric mass in the anterior portion of the fetal neck corresponding to the thyroid enlargement (measurements above the 95th percentile for gestational age), polyhydramnios (not always present), and abnormal fetal neck contour [1]. On color Doppler evaluation, peripheral hyperperfusion ("peripheral vascular rim sign") supports the diagnosis of hypothyroidism with a hypertrophic but inactive thyroid gland. Diffuse parenchymal hyperperfusion (“thyroid inferno”), due to an overactive thyroid gland, is expected in hyperthyroidism [14,15]. Three-dimensional ultrasound may facilitate the parent’s understanding of the fetal goiter [16] and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be useful for evaluating the compression and patency of the trachea and esophagus [17].

Fetuses of mothers with Graves' disease are at risk of developing either hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. In these patients, congenital goitrous hypothyroidism occurs due to the transplacental passage of antithyroid drugs or inhibitory immunoglobulins, while congenital hyperthyroid goiter occurs due to the passage of antibodies against the thyroid stimulating hormone receptor [1]. In both situations, the B-mode ultrasound findings are similar, making it difficult to use ultrasound alone to distinguish between the two conditions. Assay of thyroid hormones in the amniotic fluid does not strictly reflect fetal thyroid status and reference intervals are established only for the third trimester [18]. Therefore, fetal thyroid status can only be determined with certainty by fetal blood sampling through cordocentesis, which has a complication rate of approximately 1.4% to 2.0% [19]. In an attempt to avoid invasive methods, Huel et al. [20] described an ultrasound score to predict fetal thyroid function in cases of fetal goiter, based on the color Doppler pattern of the goiter, fetal heart rate, bone maturation, and fetal mobility. Accelerated bone maturation (typical of hyperthyroidism) is suggested by the presence of a distal femoral ossification center before 31 weeks, while its absence after 33 weeks indicates delayed bone maturation and hypothyroidism. Contrary to what happens in adult life, hyperthyroid fetuses show normal movement patterns, while jerky movements are observed in most hypothyroid fetuses.

Serial ultrasound scans starting at 18 to 22 weeks of gestation and occurring every 4 to 6 weeks in pregnant women with clinical risk factors (Graves' disease with high antibody levels, antithyroid medication, iodine intake, maternal goiter) allow the identification of patients who need close monitoring, intrauterine treatment and/or emergency intervention (EXIT procedure) [1]. Non-invasive workup includes the study of maternal thyroid function, antibody status (Thyroid-Stimulating Immunoglobulin, Thyroid Peroxidase Antibody), and careful review of maternal medication including antithyroid drugs and iodine exposure [21-23]. When severe hypothyroidism is confirmed, intra-amniotic levothyroxine administration has been shown to reduce goiter size, prevent esophageal compression and the development of polyhydramnios, as well as prevent airway obstruction at birth and improve neonatal thyroid status [24]. Optimal dosing regimens are still debated, but many protocols recommend 200–400μg levothyroxine every 1 to 2 weeks until delivery, adjusting to biochemical response [24-26]. With prompt postnatal therapy, neurodevelopmental outcomes are generally good, though some cases may still have subtle cognitive or motor deficits, especially if untreated prenatally [27].

Conditions that should be considered in the differential diagnosis of fetal goiter are fetal neck masses such as teratomas, hemangiomas, lymphangiomas, hamartomas, cystic hygromas, ectopic thymus, thyroglossal duct cysts, branchial cleft cysts, and cervical neuroblastomas. Many of these formations are usually asymmetrical and can have cystic components not present in fetal goiters [1,25].

References

[1] Gómez del Rincón O and Sabrià J. Fetal Thyroid Masses and Fetal Goiter. In: Copel JA, ed. Obstetric Imaging. Fetal diagnosis and care, 3rd ed. Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, 2026; pag 171-178.e1.

[2] Hadi HA, Strickland D. Prenatal diagnosis and management of fetal goiter caused by maternal Grave's disease. Am J Perinatol. 1995 Jul;12(4):240-242.

[3] Luton D, Le Gac I, Vuillard E, et al. Management of Graves' disease during pregnancy: the key role of fetal thyroid gland monitoring. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Nov;90(11):6093-6098.

[4] Mastrolia SA, Mandola A, Mazor M, et al. Antenatal diagnosis and treatment of hypothyroid fetal goiter in an euthyroid mother: a case report and review of literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28(18):2214-2220.

[5] Munoz JL. Fetal thyroid disorders: Pathophysiology, diagnosis and therapeutic approaches. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2019 Apr;48(4):231-233.

[6] American Academy of Pediatrics. Update of newborn screening and therapy for congenital hypothyroidism. Pediatrics. 2006 Jun;117(6):2290-2303.

[7] van Trotsenburg P, Stoupa A, Léger J, et al. Congenital Hypothyroidism: A 2020-2021 Consensus Guidelines Update-An ENDO-European Reference Network Initiative Endorsed by the European Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and the European Society for Endocrinology. Thyroid. 2021 Mar;31(3):387-419.

[8] van der Sluijs Veer L, Kempers MJ, Wiedijk BM, et al. Evaluation of cognitive and motor development in toddlers with congenital hypothyroidism diagnosed by neonatal screening. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012 Oct;33(8):633-640.

[9] Rastogi MV, LaFranchi SH. Congenital hypothyroidism. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010 Jun 10;5:17.

[10] Polak M, Luton D. Fetal thyroïdology. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Mar;28(2):161-173.

[11] Weiner S, Scharf JI, Bolognese RJ, Librizzi RJ. Antenatal diagnosis and treatment of a fetal goiter. J Reprod Med. 1980 Jan;24(1):39-42.

[12] Volumenie JL, Polak M, Guibourdenche J, et al. Management of fetal thyroid goitres: a report of 11 cases in a single perinatal unit. Prenat Diagn. 2000 Oct;20(10):799-806.

[13] Ribault V, Castanet M, Bertrand AM, et al. Experience with intraamniotic thyroxine treatment in nonimmune fetal goitrous hypothyroidism in 12 cases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Oct;94(10):3731-3739.

[14] Luton D, Fried D, Sibony O, et al. Assessment of fetal thyroid function by colored Doppler echography. Fetal Diagn Ther. 1997 Jan-Feb;12(1):24-27.

[15] Ceccaldi PF, Cohen S, Vuillard E, et al. Correlation between colored Doppler echography of fetal thyroid goiters and histologic study. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2010;27(4):233-235.

[16] Nath CA, Oyelese Y, Yeo L, et al. Three-dimensional sonography in the evaluation and management of fetal goiter. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Mar;25(3):312-314.

[17] Castro P, Werner H, Marinho PRS, et al. Excessive Prenatal Supplementation of Iodine and Fetal Goiter: Report of Two Cases Using Three-dimensional Ultrasound and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2021 Apr;43(4):317-322.

[18] Singh PK, Parvin CA, Gronowski AM. Establishment of reference intervals for markers of fetal thyroid status in amniotic fluid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003 Sep;88(9):4175-4179.

[19] Waller JA and Too GT. Cordocentesis and Fetal Transfusion. In: Copel JA, ed. Obstetric Imaging. Fetal diagnosis and care, 3rd ed. Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, 2026; pag 852-855.e1.

[20] Huel C, Guibourdenche J, Vuillard E, et al. Use of ultrasound to distinguish between fetal hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism on discovery of a goiter. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Apr;33(4):412-420.

[21] Luton D, Le Gac I, Vuillard E, et al. Management of Graves' disease during pregnancy: the key role of fetal thyroid gland monitoring. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Nov;90(11):6093-6098.

[22] Blumenfeld YJ, Davis A, Milan K, et al. Conservatively managed fetal goiter: an alternative to in utero therapy. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2013;34(3):184-187.

[23] Neto JF, Araujo Júnior E, Costa JI, et al. Fetal goiter conservatively monitored during the prenatal period associated with maternal and neonatal euthyroid status. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2016 Jan;59(1):54-57.

[24] Grüner C, Kollert A, Wildt L, et al. Intrauterine treatment of fetal goitrous hypothyroidism controlled by determination of thyroid-stimulating hormone in fetal serum. A case report and review of the literature. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2001 Jan-Feb;16(1):47-51.

[25] Mastrolia SA, Mandola A, Mazor M, et al. Antenatal diagnosis and treatment of hypothyroid fetal goiter in an euthyroid mother: a case report and review of literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28(18):2214-2220.

[26] Nemescu D, Tanasa IA, Stoian DL, et al. Conservative in utero treatment of fetal dyshormonogenetic goiter with levothyroxine, a systematic literature review. Exp Ther Med. 2020 Sep;20(3):2434-2438.

[27] Hauri-Hohl A, Dusoczky N, Dimitropoulos A, et al. Impaired neuromotor outcome in school-age children with congenital hypothyroidism receiving early high-dose substitution treatment. Pediatr Res. 2011 Dec;70(6):614-618.

Discussion Board

Winners

Javier Cortejoso Spain Physician

Alexandr Krasnov Ukraine Physician

Mayank Chowdhury India Physician

Boujemaa Oueslati Tunisia Physician

Aysegul Ozel Turkey Physician

tina walden United States Sonographer

Muradiye YILDIRIM Turkey Physician

Deval Shah India Physician

Sonio Sonio France AI

Stanislava Kacalova United States

Fred Pop Uganda Sonographer

Annette Reuss Germany Physician

Albert Guarque Rus Spain Physician

Elvira del Rosario Cienfuegos Rojas Peru Physician

Carmie Cee Australia Physician

ANDRES ARENCIBIA MOLINA United States Physician

Gustavo Costa Henrique Brazil Physician