Case of the Week #552

(1) Belveder Centre: Centre de Médecine et d’Echographie Materno-Fœtales, Tunis, TUNISIE; (2) St Mary's Medical Center, San Francisco, California, United States

Posting Dates: February 1 - February 14, 2022

Case Report: A young, nonconsanguineous couple without relevant past medical history were referred at 34 weeks gestation. The first two ultrasound examinations were normal. Fetal biometry at 34 weeks showed an estimated fetal weight in the 4th percentile (1772g), a head (285.2mm) and abdominal circumference (262.9mm) <3rd percentile, humerus length was normal (56.9mm). A repeat ultrasound examination at 37 weeks gestation confirmed the findings indicated below.

View the Answer Hide the Answer

Answer

We present a case of Trisomy 18.

Second trimester serum markers were performed at 16 weeks and were interpreted as having 1 in 10,000 risk for trisomy 21 and 1 in 2,814 risk of trisomy 18.

Our ultrasound demonstrated the following findings:

- Fetal growth restriction (5th percentile)

- Microcephaly (head circumference <3rd percentile)

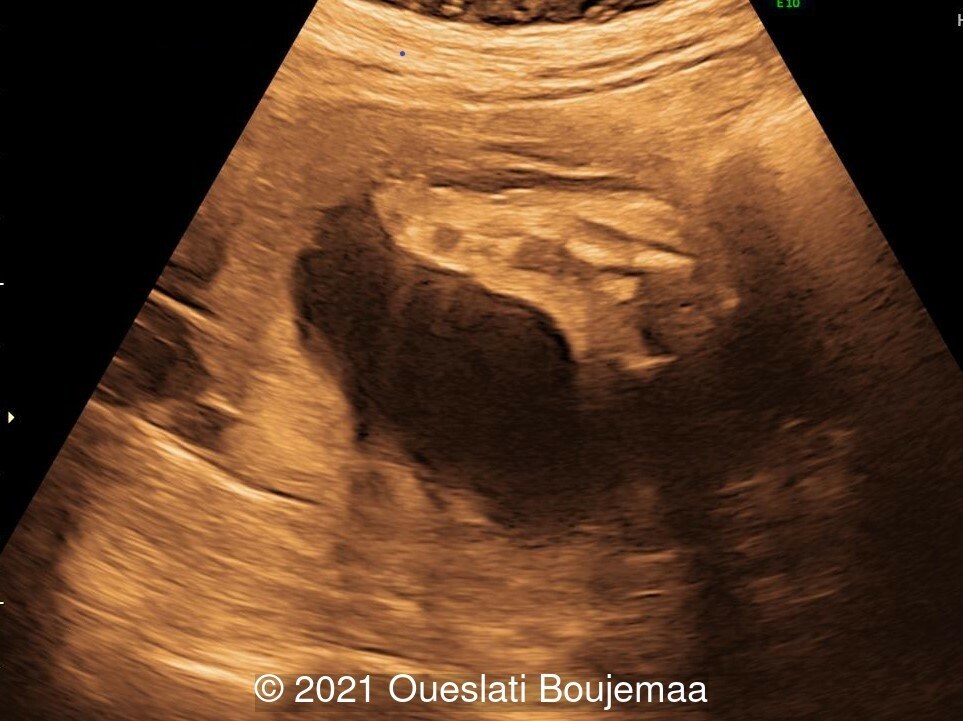

- Cerebellar hypoplasia

- Enlarged cisterna magna (cerebellomedullary cistern) with Blake's pouch cyst

- Facial dysmorphism with retrognathia

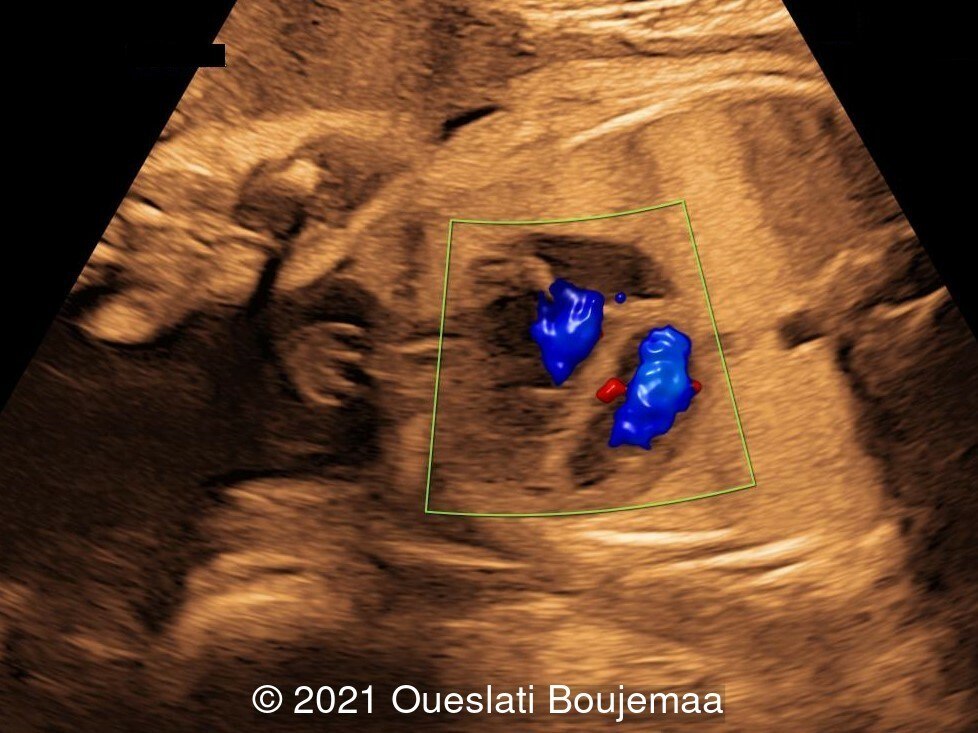

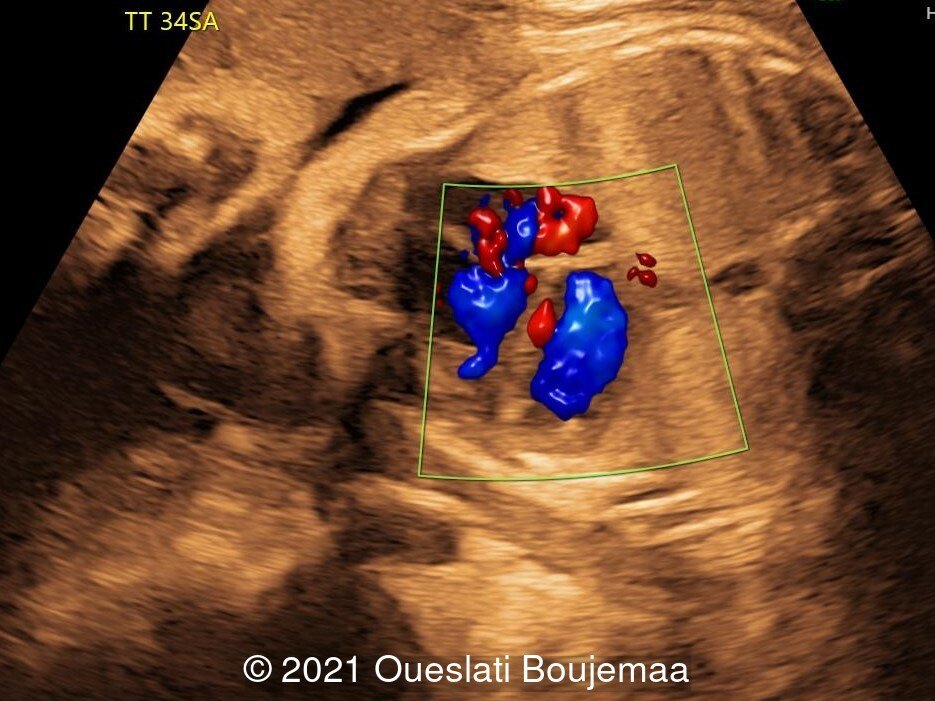

- Cardiac malformation with ventricular septal defect and linear insertion of the atrioventricular valves

- Lower extremities show “sandal gap” (wider gap between the first and second toe), and rocker-bottom feet with prominent heels

Our initial concern was trisomy 18. An amniocentesis was performed and confirmed the diagnosis. A female neonate was delivered at 40 weeks gestation with a birthweight of 2100 grams. Physical examination confirmed the malformations of the extremities and facial dysmorphism. The infant was admitted to the hospital for respiratory distress. Postnatal echocardiography confirmed a ventricular septal defect and linear insertion of the atrioventricular valves. Additionally, there was an atrial septal defect. Postnatal karyotype confirmed Trisomy 18. The infant died at 3 months of age.

Discussion

Trisomy 18, also known as Edwards syndrome, is a disorder caused by an extra chromosome 18 and was first described in 1960 by Edwards [1] and Smith [2]. Trisomy 18 is the second most common autosomal trisomy syndrome after Trisomy 21 and has a prevalence of approximately 1 in 8,600 liveborn infants [3]. Complete or full trisomy 18 is the most common form occurring in about 94% of cases. In individuals carrying mosaic trisomy 18, both a complete trisomy 18 and a normal cell line exist. In these cases, the phenotype is variable, ranging from complete trisomy 18 phenotype with early mortality to phenotypically normal adults, in which the mosaicism is detected after the diagnosis of trisomy 18 in a child [4].

Non-invasive screening based on maternal age, serum markers, and sonographic “soft markers” performed in the first trimester show a high sensitivity for the diagnosis of trisomy 18 [5]. The levels of human chorionic gonadotropin, unconjugated estriol, and alpha-fetoprotein are significantly lower in pregnancies

with trisomy 18 compared to normal pregnancy. The most common “soft markers” detected by ultrasound are nuchal fold thickness and absence or hypoplasia of the nasal bone [6]. In a prospective study that evaluates these signs in screening for common aneuploidies, nuchal fold thickness and absent nasal bone identifies two-thirds of fetuses with Trisomy 18 and 13 [7]. By including the evaluation of reversed flow in the ductus venosus and the tricuspid valve regurgitation, the detection rate of trisomy 18 and 13 increases significantly [7].

Other structural anomalies detected on prenatal ultrasound can include growth retardation, cerebral anomalies such as abnormal corpus callosum, ventriculomegaly, and spina bifida, abnormalities of the extremities such as overlapping of hands fingers (second and fifth on third and fourth respectively), as well as polyhydramnios, strawberry-shaped” cranium (brachycephaly and narrow frontal cranium), choroid plexus cyst, congenital heart defects, omphalocele, and single umbilical artery [6,8]. Growth retardation and polyhydramnios may be more common later in gestation [9]. One or more sonographic anomalies are detected in over 90% of fetuses, and two or more abnormalities are present in 55% of cases [8].

The likelihood of survival to term increases with gestational age: 28% survival at 12 weeks, 35% at 18 weeks and 41% at 20 weeks [10]. More commonly, the prenatal diagnosis of trisomy 18 leads to the decision of pregnancy termination in 86% of cases [11]. At birth, there is significant risk of infant mortality, as well as psychomotor and cognitive disability. Approximately 50% of babies with trisomy 18 live longer than 1 week, and 5-10% of children survive beyond the first year [12,13]. The recurrence risk, for a family with a child with complete trisomy 18 is usually stated at 1% [12].

References

[1] Edwards JH, Harnden DG, Cameron AH, et al. A new trisomic syndrome. Lancet 1960, 1:787–789.

[2] Smith DW, Patau K, Therman E, et al. A new autosomal trisomy syndrome: multiple congenital anomalies caused by an extra chromosome. J Pediatr 1960, 57:338–345.

[3] Crider KS, Olney RS, Cragan JD. Trisomies 13 and 18: population prevalences, characteristics, and prenatal diagnosis, metropolitan Atlanta, 1994-2003. Am J Med Genet 2008, 146A:820–826.

[4] Tucker ME, Garringer HJ, Weaver DD: Phenotypic spectrum of mosaic trisomy 18: two new patients, review of the literature and counseling issues. Am J Med Genet 2007, 143A:505–517.

[5] Perni SC, Predanic M, Kalish RB, et al. Clinical use of first-trimester aneuploidy screening in a United States population can replicate data from clinical trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006, 194:127–130.

[6] Sepulveda W, Wong AE, Dezerega V. First-trimester sonographic findings in trisomy 18: a review of 53 cases. Prenat Diagn 2010, 30:256–259

[7] Geipel A, Willruth A, Vieten J, et al. Nuchal fold thickness, nasal bone absence or hypoplasia, ductus venosus reversed flow and tricuspid valve regurgitation in screening for trisomies 21, 18 and 13 in the early second trimester. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2010, 35:535–539.

[8] Viora E, Zamboni C, Mortara G, Stillavato S, Bastonero S, Errante G, Sciarrone A, Campogrande M: Trisomy 18: fetal ultrasound findings at different gestational ages. Am J Med Genet 2007, 143A:553–557

[9] Liang ST, Yam AWC, Tang MHY, et al. Trisomy 18: The value of late prenatal diagnosis. European J Obstet & Gynecol and Reproduc Biol 1986, 22:95-97.

[10] Morris JK, Savva GM. The risk of fetal loss following a prenatal diagnosis of trisomy 13 or trisomy 18. Am J Med Genet 2008, 146A:827–832.

[11] Irving C, Richmond S, Wren C, et al. Changes in fetal prevalence and outcome for trisomies 13 and 18: a population-based study over 23 years. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2011, 24:137–141.

[12] Root S, Carey JC. Survival in trisomy 18. Am J Med Genet 1994, 49:170–174.

[13] Rasmussen SA, Wong L, Yang Q, et al. Population-based analyses of mortality in trisomy 13 and trisomy 18. Pediatrics 2003, 111:777–784.

[14] Cereda A, Carey JC. The trisomy 18 syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012 Oct 23;7:81.

Discussion Board

Winners

Fatih ULUC Turkey Physician

Suat İnce Turkey Physician

KAORU YAMASHITA Japan Physician

Amparo Gimeno Spain Physician

Laurie Briare United States Sonographer

Sonio Sonio France AI

Nina Lübke United States

Mesud Sehic Bosnia and Herzegovina Physician